Long before indoor–outdoor living became an architectural buzzword, Frank Lloyd Wright was already redrawing the line between shelter and landscape. While European modernists such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe explored an aesthetic rooted in efficiency and industry, Wright looked instead to the earth itself.

His Prairie Houses stretched low and calm across the land, their generous roofs extending over terraces and continuous bands of windows framing the horizon. Each building seemed to grow from its site.

Early twentieth-century buildings relied on load-bearing walls that dictated room divisions and enclosed spaces. Modernist architects broke free from that logic by introducing steel framing, a technique borrowed from industrial buildings. Once the beams carried the weight, the walls no longer needed to support anything. They could instead become transparent.

When Wright’s ideas reached California, they met a climate and culture ready to evolve them. Architects like Richard Neutra, Rudolf Schindler, and later Pierre Koenig or Craig Hellwood, brought together his organic principles with the clarity of European modernism. Their work responded to sunlight, breeze, and landscape, creating homes that felt alive and open to the world.

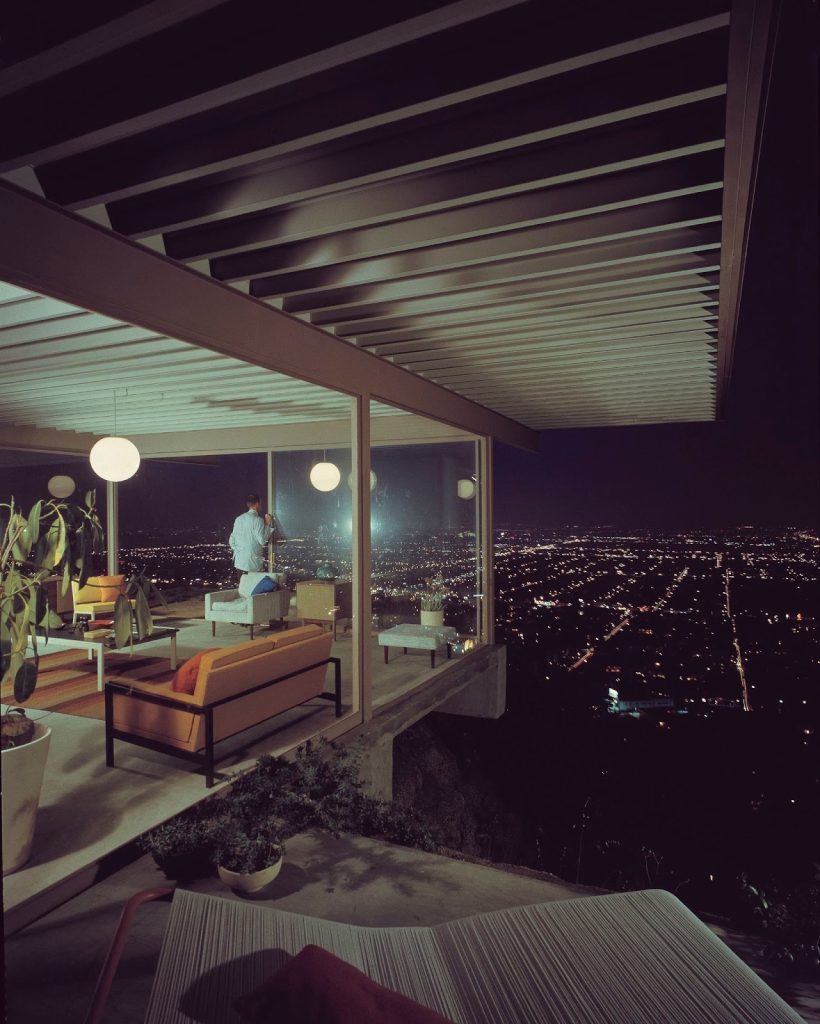

This shift changed everything. Entire façades now dissolve into view. Koenig’s Case Study House #22 in Los Angeles appears to hover in the air, its glass walls held between slender steel lines. Neutra’s Lovell Health House, built two decades earlier, used its steel skeleton to open wide panes of glass toward sun, air, and vista. These were not decorative flourishes but experiments in how construction could shape sensation.

John Lautner extended the same idea into daring new forms. His Eppstein House (1953), set among Michigan’s trees, radiates from a stone core into triangular wings of glass that open directly into the forest.

True openness also depended on movement. The sliding glass wall, so common today, was revolutionary in the 1940s. Inspired by Japanese shoji screens, architects adapted the idea using modern materials.

Charles and Ray Eames designed their 1949 Pacific Palisades home as a flexible kit of parts made from steel, glass, and colored panels. Each component could be shifted or removed, allowing the house to change with light, air, and season.

In a similar spirit, Cliff May’s ranch houses used sliding doors that vanished into wall pockets, transforming patios into living rooms. These designs were climate-smart, created to cool naturally and connect life indoors with the air outside.

Indoor–outdoor living endures because it expresses a belief that still feels modern. A home can be both structure and landscape, both shelter and horizon. It can hold the light and air in equal measure, reminding us that the most timeless form of modernism is the one that listens to its surroundings.